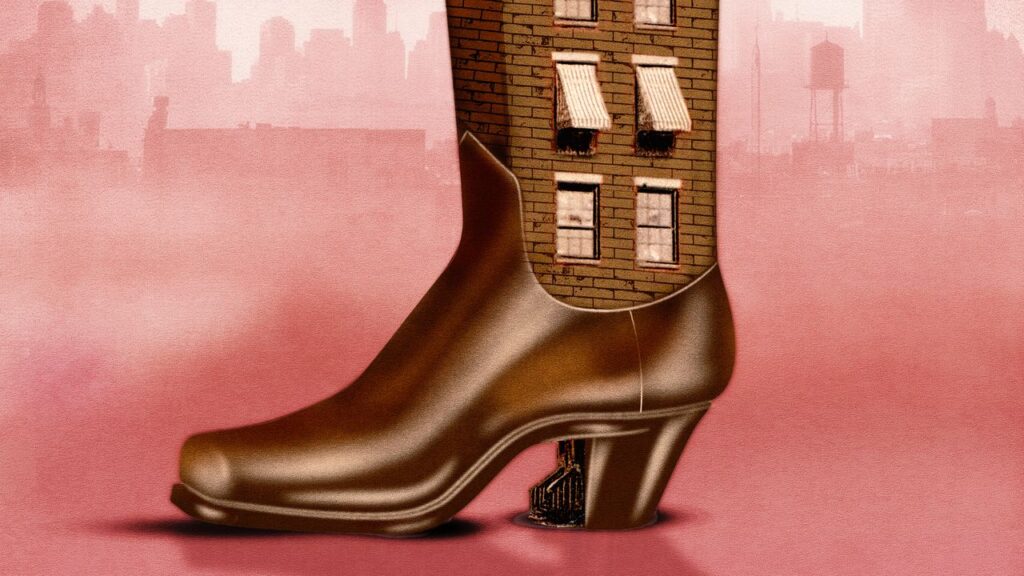

Evie Cavallo is a younger lady who lives in a shoe. To be particular, she rents a twenty-foot-tall cowboy-boot-shaped constructing, with an industrial-grade kitchen and deteriorating bistro chairs. She has to tell confused guests, repeatedly, that that is her residence. What is that this doing to her psychologically, Evie wonders. Additionally: might or not it’s true? “Dwelling,” Emily Hunt Kivel’s kooky, endearing fairy story of a début novel, is within the wobbly line between what’s actual and what’s not, and in the best way that saying issues could make them so.Evie’s hero’s journey begins, as so many do, with an issue that spurs her to motion: she, together with each different renter in New York Metropolis, is being evicted to make means for trip houses, in a surreal, class-stratifying upheaval harking back to the pandemic lockdowns. Entitled, considerably resourceful, and calmly employed, Evie assumes she’s going to determine one thing out. She disdains her neighbors’ plan to turn into Tenants in Frequent with six others. “They’d share one sock,” Evie thinks, later telling herself “there was no means . . . she was sharing a sock.” Others make plans to maneuver close to household. Evie, although, has no such choice. Each of her dad and mom have died, and her sister, Elena, lives in a hippie psychiatric establishment in Colorado. So Evie makes her option to Gulluck, Texas, to impose on a distant cousin she has by no means met. She has no need to depart Brooklyn, or to see the remainder of the nation. “I’ll be again,” she tells her landlord’s portly, benevolent son Obed when leaving New York. “I dwell right here.” She will be able to work her graphic-design job remotely within the meantime.In Texas, a baffled Evie turns into alert to her environment: she notices that what appear to be home windows are literally work of home windows; she observes {that a} group of passersby appeared, at first, to be a portray of pedestrians. “Gulluck,” she thinks, “made no sense.” However, like several fairy-tale heroine, she swiftly finds helpers. Her cousin, a real-estate agent, assists her in finding the boot. Her new boyfriend, Bertie, a good-natured key-maker who’s both enchanted or simply appears that option to Evie as a result of she’s falling in love with him, orients her in her new residence. A sage adolescent cousin tells her: “You reside right here now.” However when Evie learns that Elena’s establishment is teetering towards the cultish, she embarks on a journey to rescue her—a mission she appears unequipped to hold out. “She would get her sister,” Kivel writes, with attribute understatement, “no matter that entailed.”That the evictions are underneath means on web page 1 of the ebook signifies that Kivel spends little time on the mundanities of Evie’s life in Brooklyn. In a way, she’s a well-recognized sort of literary protagonist: she lives alone, has few buddies, and works an unfulfilling pc job. However Kivel’s isn’t a novel excited by reflecting the ennui of on a regular basis life by way of descriptions that replicate a personality’s boredom. As a substitute, it locations its topic in novel conditions, and permits her to be taught and do issues. Issues can occur, even to uninspired girls in New York, Kivel suggests. When Evie will get kicked out of her residence, following a sequence of menacing incremental shifts in housing coverage, she positive factors consciousness of herself as a personality in a bigger narrative; she realizes that “it had all led as much as this precise second, this tragicomic climax.”At first, the ebook’s canny political observations come up in opposition to Evie’s naïveté. Our protagonist is “clever, mainly, however not very perceptive,” we be taught, somebody who “wasn’t used to pondering by way of something greater than as soon as.” Within the metropolis, the narrator adroitly stories the feel of the world—the inexplicable ass spanks and wayward heads of lettuce and Cheerio-munching rats—whereas Evie lurches round, a whimsical and barely daffy enjoying monologue in her head: “Generally Evie imagined the land, the world, town round her as a cartoon neighborhood, the homes’ edges elastic like balloons.” As she progresses on her path to self-knowledge, she begins to see extra clearly, although Kivel makes the world round her all of the weirder.Kivel’s narration stays droll and nonchalant, virtually taunting the reader, as Evie’s circumstances turn into an increasing number of absurd. An eviction occurred? Yep. And her new home is a boot? O.Ok. And a lion with “ridiculous buck enamel like these in a ventriloquist dummy” crosses her path? These items occur. Numerous facet characters have a equally unfazed air: telling Evie she could fulfill a prophecy, a brand new mentor in Gulluck provides, “no strain in any respect.” Kivel retains issues shifting, with a mode that’s frank, descriptive, and dry. “Hastily she had a home. That home was a shoe,” she writes. “The following chapter occurred in a whirlwind, the best way many subsequent chapters of many tales do.” If the primary pages of the ebook counsel the immovability of the established order, Kivel intervenes by rendering a world during which the principles can change at any second.A lot of Evie’s new understanding, of herself and of her atmosphere, originates from these round her, particularly her new boyfriend. “You’re a type of hero,” Bertie tells her. “We’re each heroes.” And it’s Bertie who helps her unlock a way of company, by encouraging her to take up a brand new vocation, as a cobbler. Evie, who firstly of the ebook is within the camp of idle, underemployed protagonists that stud a lot of latest fiction, begins to seek out which means in her work. Her graphic-design job—a gig that positioned her in “a league of sullen, fairly girls who . . . cultivated their eyebrows and earrings”—had largely concerned “selecting typefaces and superimposing them onto pictures taken by another person.” Her method to shoemaking, in distinction, is sensual and responsive, rendered in lush, winding sentences that mimic the objects’ well-honed contours. In a single early creation, Kivel writes:The heel, a easy block she’d carved with waves, just like the ripples on Lake Unknown, was stitched in a good black thread to the matte crimson leather-based counter, which led seamlessly into the quarter—the part that lined the within center of the foot, the softest and most susceptible half.Evie’s shoemaking instructor quickly tells her that she is able to go away class and exit on her personal, seemingly a wish-fulfilling analogue of the M.F.A. classroom. (Kivel has an M.F.A., and has taught inventive writing.) One wonders if the ebook’s religion within the redemptive energy of craft, and the bounds of the classroom, echoes the novelist’s personal philosophy.To Kivel’s credit score, these passages on the ardor of creation are a few of the solely elements of the ebook that appear primarily based on a author’s life. “Dwelling” is squarely focussed on what might occur in a world that’s deeply, invigoratingly made up. Allusions to myths, fables, and riffs on widespread idioms abound, a lot of them evocative and fairly humorous. The sky over Gulluck recollects an illustrated kids’s Bible. Evie’s outdated boss, sending his spaniels to security in a helicopter, holds them up as if he have been “an unwavering Abraham with two miniature Isaacs.” A few of these prospers really feel a contact gratuitous: milk is spilled; repeated Amelia Bedelia-esque references are made to Evie’s sister dropping her marbles; and, in fact, there’s the title—sure, this Eve bites into an apple. The allusions can appear decorative, however additionally they remind us that Evie’s world is very similar to our personal, solely stranger: the identical outdated tales repeat themselves, simply not in the best way you’d count on.“Dwelling” is amongst a crop of novels this 12 months about lonely younger girls who channel their disaffection into lengthy, uncommon quests. Sophie Kemp’s début novel, “Paradise Logic,” narrated in a deranged, headlong type, spends its prologue teeing up a prophecy (foretold “from the second she was bornth”), earlier than sending its protagonist, a jarringly jejune twenty-three-year-old Brooklynite named Actuality, on a journey to turn into “the best girlfriend of all time” to a loser grad pupil named Ariel. (Alongside the best way, she’s helped by obscure medicine, power drinks, and interventions from speaking animals and bizarre ladies.) In Brittany Newell’s “Comfortable Core,” a San Francisco ghost story of kinds, a intercourse employee named Ruth goes on a journey to seek out her lacking ex-boyfriend. Although not explicitly fantastical, there’s a layer of the surreal—or is it simply paranoia and hallucination that make Ruth assume she sees him on the bus cease, on sidewalks, within the membership? In these books, younger girls are constrained by the calls for of femininity, but they embrace the total vary of ways—and antics—at their disposal to achieve a way of management. They dwell of their our bodies; they spend little time on their telephones. Whilst their worlds are distorted, they adapt.In “Dwelling,” Kivel cribs the plot conventions of fairy tales, and their strident ethical logic, too. “The state of housing throughout the nation was a degree of nationwide satisfaction or a catastrophic embarrassment, relying on whom you requested,” the narrator intones, early on. She threads express commentary on the housing disaster by way of the ebook: Elena turns into imperilled after a rental developer buys the land that homes her establishment; a teen-age cousin journals about his fears that he could by no means afford to depart his dad and mom’ residence in Gulluck. True to fairy-tale tropes, Evie’s landlord, Edita, has an exterior that conveys her hideous character, with lengthy fingernails and steam erupting from her ears. When Evie returns to the outdated residence, Edita taunts her with reminiscences of her pathetic previous as a Brooklyn renter: “What a lonely, lonely woman. She has no buddies, she has no household, she doesn’t do something, nothing, simply goes to work and again once more.”It ought to come as no shock that Evie will get a cheerful ending in spite of everything this—that after finishing a number of feats of bravery, with the assistance of her new buddies, she returns safely to the boot. One would possibly detect a hint of pessimism in Kivel’s social critique right here, within the implication that discovering all of this—a wealthy group, a satisfying vocation, an inexpensive place to dwell—is the stuff of fantasy. (Or not less than requires leaving New York.) Evie leans on a little bit of magic, it’s true, however what she truly positive factors from her journey is way extra modest: sincerity, dedication, openness to the world. She goes from dismissing the shared sock to residing in a shoe with nearly everybody she is aware of. ♦

Trending

- Whisky industry faces a bleak mid-winter as tariffs bite and exports stall

- Hollywood panics as Paramount-Netflix battle for Warner Bros

- Deal or no deal? The inside story of the battle for Warner Bros | Donald Trump

- ‘A very hostile climate for workers’: US labor movement struggles under Trump | US unions

- Brixton Soup Kitchen prepares for busy Christmas

- Croda and the story of Lorenzo’s oil as firm marks centenary

- Train timetable revamp takes effect with more services promised

- Swiss dealmaking surges to record highs despite strong franc