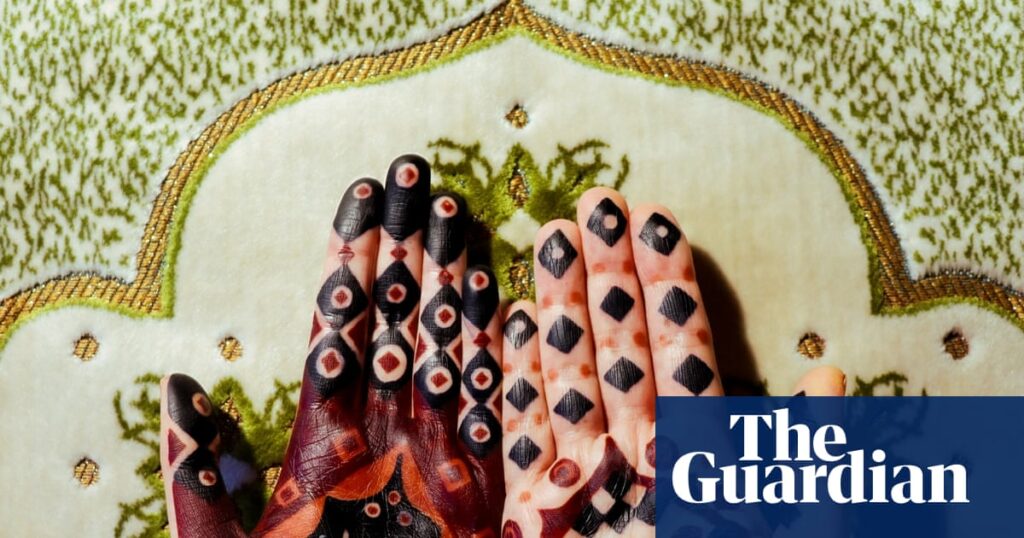

The night time earlier than Eid, plastic chairs line the pavements of busy British excessive streets from London to Bradford. Ladies sit elbow-to-elbow beneath shopfronts, arms outstretched as artists swirl cones of henna into intricate curls. For £5, you’ll be able to stroll away with each palms blooming. As soon as confined to weddings and residing rooms, this centuries-old ritual has spilled out into public areas – and immediately, it’s being reimagined totally.Lately, henna has travelled from household properties to the purple carpet – from actor Michaela Coel’s Sudanese motifs on the Toronto movie pageant to Katseye singer Lara Raj’s henna decor on the 2025 Video Music awards. Youthful generations are utilizing it as artwork, political expression and cultural affirmation. On-line, the urge for food is growing – UK searches for henna reportedly rose by almost 5,000% final yr; and, on social media, creators share the whole lot from fake freckles made with henna to five-minute floral design tutorials, exhibiting how the dye has tailored to fashionable magnificence tradition.But, for many people, the connection with henna – a paste pressed into cones and used to quickly stain pores and skin – hasn’t all the time been uncomplicated. I keep in mind sitting in salons in Birmingham once I was a teen, my arms adorned with contemporary henna that my mom insisted would make me look “presentable” for particular events, weddings or Eid. On the park, strangers requested if my little brother had scribbled on me. After portray my nails with henna as soon as, a classmate requested if I had frostbite. For years after, I hesitated to put on it, self-conscious it could draw undesirable consideration. However now, like many different younger individuals of color, I really feel a stronger sense of pleasure, and discover myself wanting my arms adorned with it extra usually.Reclaiming the shape … the members of artist collective HuqThat. {Photograph}: Arshpreet KhangurhaThis thought of reclaiming henna from cultural erasure and appropriation resonates with HuqThat, a six-member artist collective based mostly in London redefining henna as a official artwork type. Based in 2018, HuqThat’s work has adorned the arms of singers akin to Pleasure Crookes and so they have labored with Nike and Converse. “There’s been a cultural shift,” says Ruqaiyyah Patel, who joined the collective two years in the past. “Persons are actually proud these days. They could have handled racism, however now they’re coming again to it.”Henna, derived from the Lawsonia inermis shrub, has colored pores and skin, cloth and hair for greater than 5,000 years throughout Africa, south Asia and the Center East. Early traces have even been discovered on the our bodies of Egyptian mummies. Often called mehndi, ḥinnāʾ, lalle and extra relying on area or language, its makes use of are huge: to chill the physique, dye beards, bless newlyweds, or to easily beautify. However past aesthetics, it has lengthy been a vessel for neighborhood and self-expression; a method for individuals to assemble and proudly put on tradition on their our bodies.Henna designs by HuqThat. {Photograph}: HuqThat“Henna is for the plenty,” says Patel. “It comes from working individuals, from villagers who develop the plant.” Her colleague, Nuzhat El Agabani, provides: “We would like individuals to grasp henna as a official artwork type, similar to calligraphy.”Their work has appeared at fundraisers for Palestine and Sudan, in addition to at Satisfaction occasions. “We needed to make it an inclusive house for everybody, particularly queer and trans individuals who may need felt excluded from these traditions,” says El Agabani. “Henna is such an intimate factor – you’re entrusting the artist to take care of a part of your physique. For queer individuals, that may be demanding should you don’t know who’s protected.”Their strategy mirrors henna’s versatility: “Sudanese henna is completely different from Ethiopian, north Indian to south Indian,” says El Agabani. “We tailor the designs to what every individual connects with most,” provides Patel. Shoppers, who range in age and background, are inspired to carry private references: jewelry, poetry, cloth patterns. “Somewhat than copying on-line designs, I need to give them alternatives to have henna that they haven’t seen earlier than.”For Aminata Mboup, an industrial designer and sculptor based mostly in Toronto and Dakar, Senegal, fuddën (henna in Wolof) connects her to her Senegalese roots. She makes use of jagua, a pure dye from the jenipapo, a tropical fruit native to the Americas, that stains deep blue-black. “The darkened fingertips had been one thing my grandmother all the time had,” she says. “After I put on it, I really feel as if I’m getting into womanhood, an indication of grace and class.”Multidisciplinary artist Aminata Mboup shows her henna designs. {Photograph}: Courtesy of Aminata MboupMboup, who has garnered consideration on social media by showcasing her stained arms and private fashion, now ceaselessly wears henna in her on a regular basis life. “It’s essential to have it exterior particular events,” she says. “I carry out my Blackness day-after-day, and this is without doubt one of the methods I do this.” She describes it as a declaration of id: “I’ve an indication of the place I’m from and who I’m proper right here on my arms, which I take advantage of for the whole lot, day-after-day.”Making use of henna has turn out to be meditative, she says. “It forces you to pause, to sit down with your self and join with people who got here earlier than you. In a world that’s all the time dashing, there’s pleasure and relaxation in that.”Pavan Ahluwalia-Dhanjal, founding father of the world’s first henna bar. {Photograph}: Omer JanjuaPavan Ahluwalia-Dhanjal, founding father of the world’s first henna bar, in London’s Selfridges, and holder of two Guinness World Data for quickest henna utility, recognises its multiplicity: “Individuals use it as a political factor, a cultural factor, or simply for magnificence – and I respect all of that.” She started experimenting with it at a household wedding ceremony. “Nobody took me critically, not even my very own tradition,” she says. “Individuals knew they may most likely get it finished cheaper in a close-by store or home.” Then, when she went on Dragons’ Den in 2024, “I used to be instructed henna wouldn’t transcend my neighborhood. However for the primary six years, most clients weren’t from my tradition in any respect.”Ahluwalia-Dhanjal says her henna bar has attracted “vacationers and western individuals” and, solely previously couple of years, individuals of south Asian background. “I now have a workforce of 25 pro-artists who do henna workshops throughout the UK and fly to Los Angeles,” she says. She desires henna to be “as accessible as lipstick or nail polish”. “It’s a magnificence staple,” she says.Its newfound visibility hasn’t come with out stress; the superb line between appreciation and appropriation is commonly blurred when individuals borrow the artwork with out understanding its roots. Ahluwalia-Dhanjal is pragmatic: “Some individuals suppose it’s just for festivals, weddings or south Asian individuals. The truth that it’s persistently bought all year long says quite a bit about what number of cultures admire henna.”Throughout continents and generations, henna’s that means continues to stain deeply. For Mboup, that is the purpose. “Henna jogs my memory that there’s energy and advantage in what’s hid and guarded. It’s a stain – and it’s mine.”

Trending

- Whisky industry faces a bleak mid-winter as tariffs bite and exports stall

- Hollywood panics as Paramount-Netflix battle for Warner Bros

- Deal or no deal? The inside story of the battle for Warner Bros | Donald Trump

- ‘A very hostile climate for workers’: US labor movement struggles under Trump | US unions

- Brixton Soup Kitchen prepares for busy Christmas

- Croda and the story of Lorenzo’s oil as firm marks centenary

- Train timetable revamp takes effect with more services promised

- Swiss dealmaking surges to record highs despite strong franc