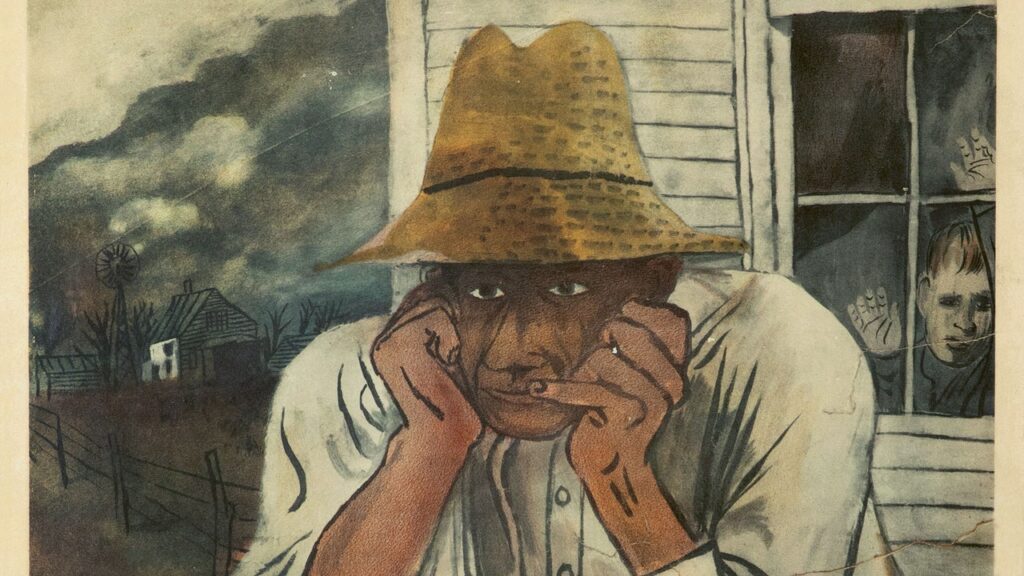

From the late nineteen-forties by the mid-fifties, Ben Shahn was one of the vital in-demand artists in America. Whether or not you had been mailing a bundle at a put up workplace, flipping by a nationwide journal, or watching CBS, you’d have seen Shahn’s chiselled line and patchy brushwork. Firms and personal collectors had been hungry for his work; union halls and authorities companies plastered their partitions along with his murals and posters; and in 1947 the Museum of Fashionable Artwork topped him with a mid-career retrospective.You’d think about Shahn’s work could be supremely lovely, or no less than soothing to the attention. Oddly sufficient, it was neither. Shahn was often called a social realist: a painter of hardscrabble life who registered each spasm and twitch of the physique politic, from the Nice Despair to Vietnam. In reality, he was extra of an adman with leftist convictions, much less excited about documenting the lives of farmers and bricklayers than in boiling down an emotion into the smallest potential unit of visible which means—a clenched fist, a furrowed forehead—and speaking that emotion to as many individuals as potential. In response to his personal Whitmanic imaginative and prescient, Shahn believed he may communicate to the six million individuals who understood Norman Rockwell and to the sixty who understood Picasso’s “Guernica.” And, in some methods, he may. He was the uncommon chameleon who appealed to each company sorts and the working class, bean counters and artwork critics. In contrast with different American artists who’ve managed a repute on this scale, his closest analogue could be Dolly Parton.“Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity,” the brand new present on the Jewish Museum, is the primary retrospective of Shahn’s work in America since 1978. It reportedly had a troublesome time discovering a U.S. dwelling after it opened, at Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofía, in 2023, and one can see why. The curators appear to have licked a finger and held it to the political winds. As {the catalogue} states, the exhibition intends to learn Shahn’s work, posters, drawings, and pictures “by the lens of latest variety and fairness views.” There’s no outpouring of recent analysis, no bigger-than-ever assemblage of buried or forgotten work. As a substitute, the gambit right here is to shock-paddle Shahn again to life, as an unsung nationwide hero: a progressive who rallied to the causes of labor, civil rights, and social welfare, and whose artwork we must always respect due to his exemplary politics. The thriller that the present by no means addresses is why individuals as soon as cared a lot about his artwork—and why we must always, at the moment.Shahn was born in Lithuania in 1898, below the fist of Russian rule, and arrived at Ellis Island in 1906, with greater than 100 thousand different Jews from Jap Europe. He apprenticed as a lithographer, studying to combine acid, sharpen chisels, and prep lithography stones earlier than progressing to letters, drilling himself for months on the roman alphabet. Whereas engaged on and off, he paid his means by courses at N.Y.U., Metropolis Faculty, and the Nationwide Academy of Design, and deepened his arts schooling on journeys to Europe and North Africa. His most essential affect, although, remained lithography—its limestone and grease pencil—and the engraver’s chisel. These instruments molded Shahn as a draftsman and gave him a signature fashion, even in his work. Take a look at virtually any canvas and you’ll see his tough black line at work, corralling and structuring muddy splotches of paint.The present gives no glimpse of Shahn’s apprentice years or French-modernist flailing, when he fell below the spell of Cézanne, Matisse, and Rouault, and as an alternative begins with Shahn’s most well-known piece: “The Ardour of Sacco and Vanzetti” (1931-32). It often lives downtown, on the Whitney Museum, and right here it’s mounted in order that it may be seen from the sidewalk on Ninety-second Avenue, even earlier than you hit the safety line. In 1927, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two working-class Italian anarchists charged with homicide, had been despatched to the electrical chair in Massachusetts, setting off protests all over the world. Shahn places the our bodies of Sacco and Vanzetti on the foot of the portray, of their coffins, and above them the three members of the Lowell Committee, who affirmed the responsible verdict. The piece, because the title suggests, is a modern-day Crucifixion.When Shahn didn’t like somebody, he may paint them very properly as a lifeless fish. The pores and skin tones of the judges vary from bruised potato to moist brown paper bag, and their our bodies are cartoonishly flat. Shahn, impressed by Italian fresco, most popular egg tempera to grease, as a result of it dried rapidly and left little time for revision—forcing his hand into a call. Although different American painters reminiscent of Thomas Hart Benton, Andrew Wyeth, and George Tooker additionally used tempera, Shahn’s surfaces had been persistently coarser. Simply have a look at any individual in a portray by Tooker. You possibly can drizzle olive oil on a kind of arms or legs and swallow it like a noodle. With Shahn, it’s all roughage.The Nice Despair was oddly good to Shahn. Despite the fact that lithography work was exhausting to return by, he frolicked his shingle as a painter and located illustration at Downtown Gallery, by means of Edith Halpert, who exhibited his cycle of twenty-three items on the Sacco and Vanzetti trial to crucial success and delicate scandal. The remainder of Shahn’s résumé from the thirties reads like that of a lefty artist plucked from central casting. He’s tapped by Diego Rivera to help on essentially the most notorious mural of the last decade, “Man on the Crossroads” (torpedoed by Nelson Rockefeller for its inclusion of Lenin); he joins the Artists Union and edits its journal Artwork Entrance; he begins designing posters for the Resettlement Administration and goes to bat for F.D.R. and the New Deal. “Propaganda,” he stated, “is a holy phrase when it’s one thing I imagine in.”The important thing work to emerge from this era just isn’t an enormous mural fee—such because the forty-five-foot narrative mudslide of the Jewish-immigrant story housed in an elementary faculty in New Jersey—however Shahn’s images, a medium he initially knew nothing about. As luck had it, he shared a studio with the good documentary photographer Walker Evans. In an interview from the sixties, Shahn recalled Evans instructing him easy methods to shoot. “He says, ‘Effectively, it’s very straightforward, Ben. F9 on the sunny facet of the road, F4.5 on the shady facet of the road. For a twentieth of a second maintain your digital camera regular,’ and that was all.” The Resettlement Administration despatched Shahn on a reconnaissance mission to get to know America by automotive, and through three months of driving across the South, by coal and cotton nation, he snapped round three thousand photos.Images sculpted Shahn’s eye in a means that no different medium may. It prompted him to see the incidental as a logo. A dirty shirt may communicate to the Mud Bowl, an engorged cotton sack to the evils of slavery. Shahn used an angle finder, in order that he may level the digital camera in a single route and take a photograph ninety levels to his left. Supposedly, this allowed him to seize his topics “unaware,” however that’s solely half true. Shahn’s greatest pictures present individuals each conscious and never. The exhibition catalogue has just a few wonderful examples of this which have been dropped from the present, reminiscent of “Sharecroppers’ Youngsters on Sunday, close to Little Rock, Arkansas” (1935), a masterpiece of contrasts and parallels. The facial expressions of the kids may as properly belong to totally different centuries. One lady has her face tangled up in disgust. One other, with pale eyes, is stroking her chin and appears to be experiencing all of historical past from some Archimedean level. Keep in mind, what we’re witnessing right here usually are not on a regular basis faces however faces rearranged round a stranger holding a space-age gizmo, gazing the opposite means.To see the angle finder in motion, you’ll be able to lookup Shahn’s “Self-Portrait Amongst Church Goers” (1939). The portray is a mini summa of two key tendencies working by Shahn’s work: self-quotation and cheekiness. Shahn paints himself, digital camera in hand, on the entrance of a church in Brooklyn the place a sermon criticizing considered one of his murals had been delivered. A few the grumpy churchgoers standing close by are lifted from a photograph he’d taken in Natchez, Mississippi, in 1935, stitching collectively two occasions, two locations, and two totally different media (as Shahn preferred to do). His self-presentation just isn’t that of a postmodern auteur, poised to trounce his critics, however of a goofy man off to the facet with spectator footwear, spindly legs, and ginormous palms. He’s dunking on the church and its self-serious patrons—when you squint on the church signal, it reads “IS THE GOVERNMENT FOSTERING IRRELIGION IN ART??????”—however he’s additionally dunking on himself: the artist on the fringe of the body, on the fringe of every part, all the time prodding and poking society with a stick.Mr. Spectator Footwear may stroll proper into his personal retrospective on the Jewish Museum and nobody would acknowledge him. Lest we overlook, this was an artist who made drawings of bespectacled geese and a tuxedo-wearing hen named “Mr. H. Falco Peregrinus.” For each portray of a tenant farmer is one other like “Summertime” (1949), through which a person is having an excessively intense expertise with a watermelon, or “Epoch” (1950), with slightly bald fellow doing a handstand on the heads of two cyclists, his pants scrunched up round his knees. Whereas Shahn was actually a political creature, with a fiery sense of ethical function, he wasn’t a one-dimensional Homo politicus. He had wit.In time, Shahn frightened that his creativeness was truncated by images, or that individuals thought as a lot. The Second World Warfare and the Crimson Scare drove him towards a quasi-mystical visible language, extra Marc Chagall than Diego Rivera, that relied on a rising menu of tropes: masks, rubble, blind individuals, flames. The opposite historic drive goading him on, away from social realism and towards what he known as “private realism,” was the disaster in easel portray often called Summary Expressionism. Because the story goes, Jackson Pollock stepped onto a canvas in 1947, drizzled some paint right here and there, and God reached a bony finger down from the heavens and pressed it upon the size of artwork historical past, tilting it from Europe to the USA. Nearly in a single day, Ben Shahn turned an vintage. When MOMA despatched each Shahn and Willem de Kooning to symbolize the U.S. on the Venice Biennale, in 1954, the message was clear: Behold the previous and way forward for American artwork.At the same time as Shahn racked up honorary levels and tv appearances within the fifties and sixties, he produced work that had been, for essentially the most half, unhealthy. There are many items like “Everyman” (1954) and “Existentialists” (1957), which serve up murky allegories of geopolitical drift. You possibly can see Shahn attempting to beat a path again to Picasso, if Picasso painted solely with melted popsicles and never brushes. The uncommon gems from this era are Shahn’s drawings, with their daring but stuttering line. In step with its political grasp theme, the Jewish Museum offers pencil and ink research of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Gandhi’s hand—with a beautiful little swirl for a knuckle—although we see none of Shahn’s quivering cityscapes and forests, his lovers embracing, his solitary figures floating in despair.Drawings like these usually are not instantly helpful when you’re in search of Shahn out for his political advantage. They don’t have any of the muscular function or management he injected into his work, the place the order of the day was to all the time symbolize: to take a lowly object from actuality, like a potato subject or a gnarled hand, and to remodel it right into a glowing picture round which individuals may assemble. This was the perform of artwork, as Shahn argued in a collection of lectures he gave at Harvard within the fifties. Shahn’s greatest work doesn’t want this apotheosis, although. His line can collect sufficient of the blood and feeling of the 20 th century simply by the way in which it distends and contracts below the comb. It all the time appears to be saying, “I can’t go on, I’ll go on.” It has all of the advantage of being actual. ♦

Trending

- UK can ‘lead the world’ on crypto, says City minister

- Spain’s commitment to renewable energy may be in doubt

- Whisky industry faces a bleak mid-winter as tariffs bite and exports stall

- Hollywood panics as Paramount-Netflix battle for Warner Bros

- Deal or no deal? The inside story of the battle for Warner Bros | Donald Trump

- ‘A very hostile climate for workers’: US labor movement struggles under Trump | US unions

- Brixton Soup Kitchen prepares for busy Christmas

- Croda and the story of Lorenzo’s oil as firm marks centenary